Can #Africa win as the West and #China scramble for minerals?

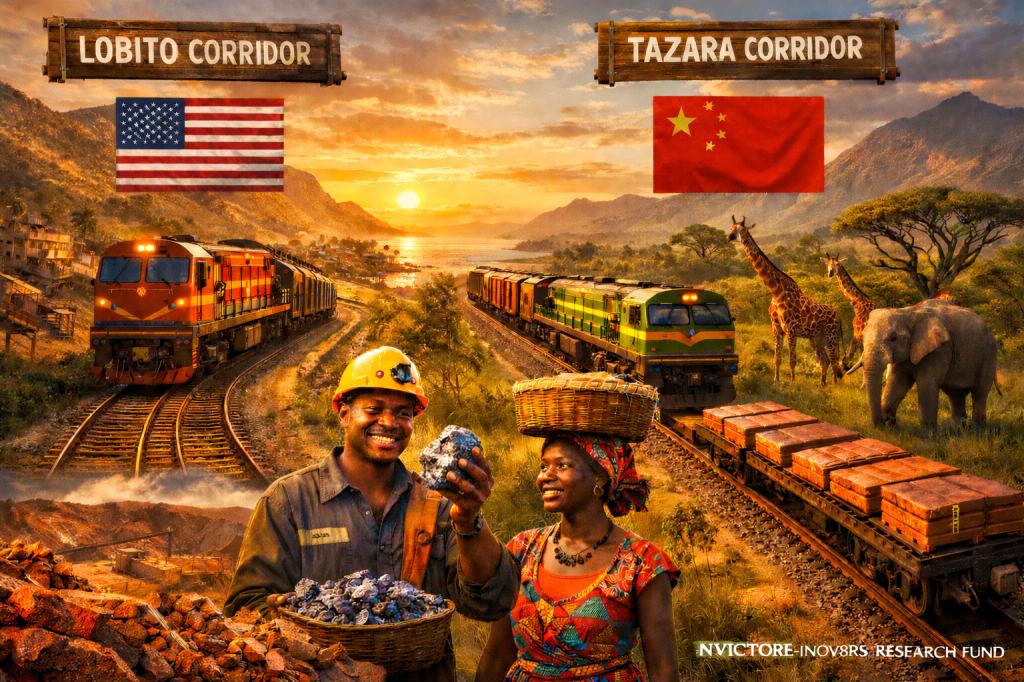

CAPE TOWN, Feb 12 (Reuters) – Two multi-billion dollar rail projects in Africa. One headed west, the other east. One backed by Western countries, the other by China. Both aiming to ship vast quantities of critical minerals. Welcome to the new scramble for Africa.

The Lobito rail corridor will cost up to $6 billion by the time it’s planned to be finished by 2030, with around 1,700 kilometres (1,050 miles) of track taking mainly copper and cobalt from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia west to the Angolan port of Lobito.

Much of the funding is coming from the United States and Europe and aims to upgrade the existing railway and build new lines in order to boost the annual capacity to 4.6 million metric tons per year.

Heading the other way east to Tanzania is the TAZARA railway, a 1,860 kilometer line that links the same mineral-rich parts of Zambia and the DRC to a port on the Indian Ocean, which offers shorter sailing times to China and other Asian markets.

Similar to the Lobito project it is a rehabilitation of an existing colonial-era railway and its Chinese backers are slated to spend around $1.4 billion to upgrade its annual capacity to 2.4 million tons.

These two projects are emblematic of how the world’s great powers are seeking to source and control the minerals needed to power industrial economies and the energy transition.

But they also show the contrasting ways that Western countries and China are trying to achieve their aims of security of supply.

Stuck in the middle are African countries, blessed by their resource endowment but cursed by a lack of coordinated policies on how to ensure they are not exploited by stronger nations, as well as too often being hobbled by poor governance and an inability to offer consistent and reliable investment regimes.

What is different this time compared to the colonial conquest of Africa two centuries ago is that African countries have far more choice.

They can set the rules and decide who they want to partner with, and if they get it correct then they stand to benefit from increased investment, jobs and revenue from taxes and royalties.

The models being offered are slightly different, insofar as the Western countries largely prefer private operators, coupled with public partnerships and funding in order to build mines and transport infrastructure.

U.S. WOOS

One of the major shifts at this week’s Mining Indaba conference in Cape Town was how the United States has changed tack, eschewing the bombastic and combative rhetoric of President Donald Trump and trying to focus on promoting trade and investment.

It is perhaps a tacit acknowledgement that insulting countries that you need for their resources is not a winning policy, but U.S. officials were out in force touting their capital for investment and their willingness to effectively re-risk mining projects by guaranteeing offtake and prices.

If the United States does go down this path, and African countries can look past the prior Trump insults and gutting of U.S. aid, there is a real possibility that new mines and infrastructure will proceed.

The planned U.S. “vault” of critical minerals will need African resources and a meeting of more than 50 countries last week shows the Trump administration appears to be serious about building and securing supplies of metals.

Will the efforts by the United States, and to a lesser extent the European Union, be enough to wean African states from Chinese investment, which has tended to be more all-encompassing as Chinese companies explore, build, operate and transport minerals.

An example is the massive Simandou iron ore mine in Guinea, currently ramping up to its 120 million tons a year capacity.

For years the project languished as Western companies struggled to mount a viable economic plan to make it work.

But Chinese investment and technical skill has brought the project to life, albeit with a minority partner in Rio Tinto and the ore from Simandou will flow almost entirely to China as a result.

The Chinese also have a strong first-mover advantage in Africa, having been active for decades.

But the question for African countries is whether China’s investment in extracting the continent’s minerals has been mutually beneficial, or whether it has been skewed towards Beijing.

The follow-up question is whether Western countries and their trading and mining companies will offer anything substantially better.

What is almost certain is that more investment is heading to exploit Africa’s mineral endowment, which will boost competition and de-risk projects.

Is the prize big enough to make everybody a winner? Yes, but it will take considerable effort and cooperation and the track record for that in Africa is patchy at best.

Source: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/can-africa-win-west-china-scramble-minerals-2026-02-12/